Leishmaniosis in humans

Leishmaniosis is a well known disease, appearing mainly in the countries of southern Europe. It is an endemic zoonosis in 88 countries around the world, although 90% of affected individuals are located in five countries: India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Brazil and Sudan.

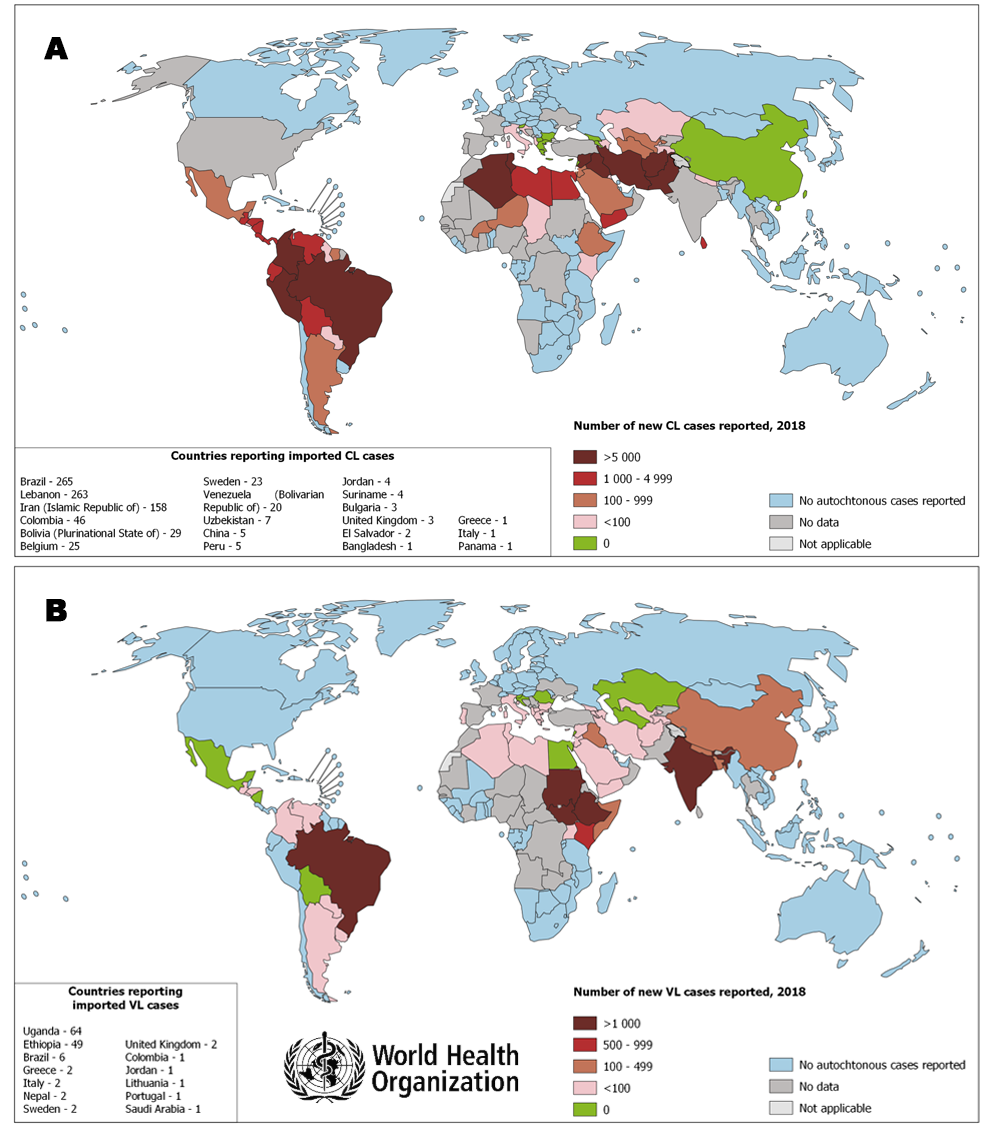

Figure. Leishmaniosis world distribution map (A) cutaneus leishmaniosis and (B) visceral leishmaniosis. WHO 2018.

According to the World Health Organization, the annual incidence is estimated to be between 1.5 and 2 million cases, the prevalence is 12 million, and the population at risk of being infected is estimated at 350 million people; WHO Technical Report Series 949. 2010).

Epidemiological surveillance in Spain started in 1982, when leishmaniosis was included in the list of notifiable diseases (EDO). Since 1993 a considerable increase in reported cases have been notified and at the same time endemic regions have been extended. In 2009 a large outbreak occurred in Fuenlabrada and other municipalities of the SO region (Humanes de Madrid, Getafe and Leganés). This outbreak is still ongoing and has so far affected more than 690 people (SNEDO 2016). In this case a new urban transmission cycle involving animal reservoirs different than dog (hares and rabbits) has been evidenced.

Real Decreto 2210/1995, de 28 de diciembre y Orden SSI/445/2015, de 9 de marzo (B.O.E. 17 marzo 2015, Sec. I. Pág. 24012)

Decreto 184/1996, de 19 de diciembre, por el que se crea la Red de Vigilancia Epidemiológica de la Comunidad de Madrid.

ORDEN 9/1997, de 15 de enero, de la Consejería de Sanidad y Servicios Sociales, para el desarrollo del Decreto 184/1996, de 19 de diciembre.

EVALUACIÓN DEL RIESGO DE TRANSMISIÓN DE LEISHMANIA INFANTUM EN ESPAÑA. OCTUBRE 2012. Documento elaborado por: Centro de Coordinación de Alertas y Emergencias sanitarias (CCAES) Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad

Leishmania transmission in humans

Parasite transmission to humans occurs by the bite of an infected sandfly. The sandfly becomes infected after biting an parasitized host . Person-to-person transmission by sexual contact, blood transfusions and the use of contaminated syringes has also been described, but they are exceptionally rare.

Leihsmaniosis symptoms in humans

Cutaneous leishmaniosis is characterized by ulcerative lesions on the skin, usually painless. The incubation period is from 2 weeks to 4 months from the bite. They are self-limiting and usually healed even without treatment. However, in some cases healing could take months and leave sequelae such as scars.

Visceral leishmaniosis or kala azar is more severe and mainly affects various organs such as the spleen, liver and bone marrow. The incubation period ranges from 10 days to 2 years (often from 2 to 4 months). Usual symptoms are fever and weight loss, followed by an increase of the size of the spleen and the liver. The onset of anemia is also common. This disease has an effective treatment, although it requires the hospitalization of the patient.

Leihsmaniosis prevention in humans

The prevention and control of Leishmaniosis require a combination of strategies, because transmission occurs in a complex biological system that involves the human host, the parasite, the vector, and, in some cases, an animal reservoir. The main strategies that should be taken into account are:

- Early diagnosis and effective management of cases reduce the prevalence of the disease and prevent disability and death.

- Vector (sandflies) control helps to reduce or interrupt the disease transmission especially in the domestic context.

- A successful disease surveillance is important. The rapid data notification is crucial for the monitorization during epidemics when there is a high rate of fatality despite treatment.

-

Animal reservoirs control is complex and must be adapted to the local situation.

- Social awareness and the strengthening of partnerships is also a key factor. Partnerships and collaboration with various stakeholders and other vector-borne diseases control programmes are essential at all levels.

The work of WHO in the fight against leishmaniosis includes the following:

- Support national programs for the control of leishmaniosis in the development of updated guidelines and disease control plans.

- Awareness-raising and advocacy activities on the global burden of leishmaniosis, and promotion of equitable access to prevention and case management.

- Development of guidelines, strategies and policy standards based on scientific data for the prevention and control of leishmaniosis, and surveillance of their application.

- Provision of technical support to Member States to create a monitoring system and mechanisms for sustainable and effective response.

- Strengthen collaboration and coordination among partners, stakeholders and other agencies.

- Monitoring the status and trends of leishmaniosis in the world and measuring progress in disease control and funding.

- Provision of diagnostic tests and anti-leishmanial drugs when they are needed.

- Promoting research to effectively fight leishmaniosis, especially with regards to safe, effective and affordable medicines, diagnostic tools and vaccines and facilitating the dissemination of research results.

In the Communityof Madrid a joint action plan is being implemented by the municipalities and the Community, whose main activities are:

- Monitoring the reservoir (dog): maintenance of serological surveillance in Animal Protection Centers (systematic check in all dogs coming in the premises and slaughter in case of positivity), reinforcement of surveillance in all potential risk foci (rehalas, etc.). Also research of the presence of other fauna that could be involved as reservoir.

- Surveillance of the vector (phlebotomine): phlebotomines capture using traps, identification of the species and identification of the presence of the parasite.

- Environmental control: identification of risk areas and application of environmental sanitation measures (dumps, parks, landfills, etc.), disinsectisation of potential sources of risk and collection of abandoned animals.

- Health education: publication and distribution of informative leaflets of the disease and its prevention, carried out in collaboration with the College of Veterinarians of Madrid.

- Control of hare and rabbit populations in risk areas.

If you live in an endemic area of Leishmania with the presence of the vector, you work outdoors in the activity period of the vector, or you sleep the warm months with the window open, and you do not protect yourself from the bites, you are more likely to acquire the infection.

Outdoors:

- If you walk in parks from dusk, or at dawn, it is advisable to wear clothes that cover the skin (long sleeves, long trousers), as well as the use of suitable repellent products taking into account the instructions of the product. If you go with baby buggies you can cover them with a mosquito net.

Indoors:

- Inside the houses, especially in low height buildings, the use of electric mosquito diffusers in the rooms is recommended, but never ultrasonic emitters, because they are innocuous to the phlebotomines. Besides, the application of long lasting insecticides in door frames and windows, as well as taking the appropriate hygienic measures in all the places that can be a mosquito shelter are suggested. Common insecticidal sprays are also valid, applying them several times a day in rooms and bedrooms.

- Installation of mosquito nets on doors and windows. These must be made of fine mesh (1-2 mm maximum).

- Using air conditioning and fans prevent the mosquitoes from flying inside the houses.

- Avoiding the accumulation of vegetal remains and debris in the surrounding of the dwelling. It may also help methods such as plastering walls cracks with mud or lime to reduce the phlebotomous population.

- Maintenance of good hygienic-sanitary conditions at home, as well as adequate housing domestic animals in enclosed spaces.

Therefore the best prevention measures would include vector control, reducing the number of infected phlebotomines, reducing the contact of insects with the human, controlling reservoirs and reducing the number of infected animals in endemic areas.

If you suspect that you have the disease, you should go to the doctor.

Leishmaniosis diagnosis in humans

The diagnosis is made by direct microscopic visualization of the parasite in smears or DNA detection by PCR techniques in bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes, blood, skin, etc. Culture can also be performed from tissue samples or bone marrow aspirates.

In addition, Leishmania antibodies can be detected by serological techniques such as IFAT (indirect immunofluorescence) or ELISA, always taking into account that it is important to carry out serum titration because individuals who are asymptomatic or those whose infection is resolved may have antibodies. On the other hand, serology is often not useful in cases of cutaneous leishmaniosis, since antibody levels are very low or nonexistent.

Leishmaniosis treatment in humans

In humans the treatment of choice is amphotericin B in the case of visceral leishmaniosis. Antimonials or pentavalent antimony salts are also used. New drugs such as miltefosine and paramomycin are also available, which can be combined with the aforementioned drugs in order to reduce their toxicity and cost.

Cutaneous leishmaniosis usually resolves spontaneously, although it usually leaves a scar in the area of the lesion.

References

- 2011. Brote comunitario de leishmaniasis en la zona suroeste de la Comunidad de Madrid. Año 2011. [Report Community outbreak of leishmaniasis in the southwest area of the Community of Madrid. Year 2011]. In Boletín epidemiológico de la Comunidad de Madrid.

- 2015. Leishmaniasis en la Comunidad de Madrid. Documentos Técnicos de Salúd Pública. Dirección General de Salud Pública.

- Arce, A., Estirado, A., Ordobas, M., Sevilla, S., Garcia, N., Moratilla, L., de la Fuente, S., Martinez, A.M., Perez, A.M., Aranguez, E., Iriso, A., Sevillano, O., Bernal, J., Vilas, F., 2013. Re-emergence of leishmaniasis in Spain: community outbreak in Madrid, Spain, 2009 to 2012. Euro. Surveill18, 20546.

- Boelaert, M., Criel, B., Leeuwenburg, J., Van, D.W., Le, R.D., Van der Stuyft, P., 2000. Visceral leishmaniasis control: a public health perspective. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg94, 465-471.

- Boggiatto, P.M., Gibson-Corley, K.N., Metz, K., Gallup, J.M., Hostetter, J.M., Mullin, K., Petersen, C.A., 2011. Transplacental transmission of Leishmania infantum as a means for continued disease incidence in North America. PLoS Negl Trop Dis5, e1019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001019

- Carrillo, E., Moreno, J., Cruz, I., 2013. What is responsible for a large and unusual outbreak of leishmaniasis in Madrid? Trends Parasitol29, 579-580. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.10.007

- Desjeux, P., 2004. Leishmaniasis: current situation and new perspectives. Comp Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis27, 305-318. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2004.03.004

- Desjeux, P., Piot, B., O'Neill, K., Meert, J.P., 2001. [Co-infections of leishmania/HIV in south Europe]. Med Trop (Mars)61, 187-193.

- Dey, A., Singh, S., 2006. Transfusion transmitted leishmaniasis: a case report and review of literature. Indian J Med Microbiol24, 165-170.

- Dujardin, J.C., Campino, L., Canavate, C., Dedet, J.P., Gradoni, L., Soteriadou, K., Mazeris, A., Ozbel, Y., Boelaert, M., 2008. Spread of vector-borne diseases and neglect of Leishmaniasis, Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis14, 1013-1018.

- Gallego, M., 2004. [Emerging parasitic zoonoses: leishmaniosis]. Rev. Sci. Tech23, 661-676.

- Gonzalez, U., Pinart, M., Sinclair, D., Firooz, A., Enk, C., Velez, I.D., Esterhuizen, T.M., Tristan, M., Alvar, J., 2015. Vector and reservoir control for preventing leishmaniasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD008736. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008736.pub2

- Gradoni, L., Gramiccia, M. 2008. Leishmaniosis. In In: OIE Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals (mammal, birds and bees), Chapter 2.1.8.

- Gramiccia, M., Gradoni, L., 2005. The current status of zoonotic leishmaniases and approaches to disease control. Int. J. Parasitol35, 1169-1180. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.001

- Jimenez, M., Gonzalez, E., Iriso, A., Marco, E., Alegret, A., Fuster, F., Molina, R., 2013. Detection of Leishmania infantum and identification of blood meals in Phlebotomus perniciosus from a focus of human leishmaniasis in Madrid, Spain. Parasitol. Res. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3406-3

- Lemrani, M., Hamdi, S., Laamrani, A., Hassar, M., 2009. PCR detection of Leishmania in skin biopsies. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries3, 115-122.

- Martin-Martin, I., Molina, R., Rohousova, I., Drahota, J., Volf, P., Jimenez, M., 2014. High levels of anti-Phlebotomus perniciosus saliva antibodies in different vertebrate hosts from the re-emerging leishmaniosis focus in Madrid, Spain. Vet. Parasitol202, 207-216. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.02.045

- Mutiso, J.M., Macharia, J.C., Kiio, M.N., Ichagichu, J.M., Rikoi, H., Gicheru, M.M., 2013. Development of Leishmania vaccines: predicting the future from past and present experience. J. Biomed. Res27, 85-102. doi: 10.7555/JBR.27.20120064

- Palatnik-de-Sousa, C.B., Day, M.J., 2011. One Health: the global challenge of epidemic and endemic leishmaniasis. Parasit Vectors4, 197. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-197

- Ready, P.D., 2010. Leishmaniasis emergence in Europe. Euro. Surveill15, 19505.

- Singh, N.S., Singh, D.P., 2009. Seasonal occurrence of phlebotominae sand flies (Phlebotominae: Diptera) and it's correlation with Kala-Azar in eastern Uttar Pradesh, India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health40, 458-462.

- Suárez, B., Isidoro, B., Santos, S., Sierra, M.J., Molina, R., Astray, J., Amela, C. 2012. Review of the current situation and the risk factors of Leishmania infantum in Spain. In Revista Española de Salud Pública, pp. 555-564.

- van Griensven, J., Carrillo, E., Lopez-Velez, R., Lynen, L., Moreno, J., 2014. Leishmaniasis in immunosuppressed individuals. Clin Microbiol Infect20, 286-299. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12556